Meeting the Goals of Value-based Care in Chronic Disease Management

Thursday, July 14, 2022

by Susan Garramone, Senior Clinical Marketing Manager - Siemens Healthineers

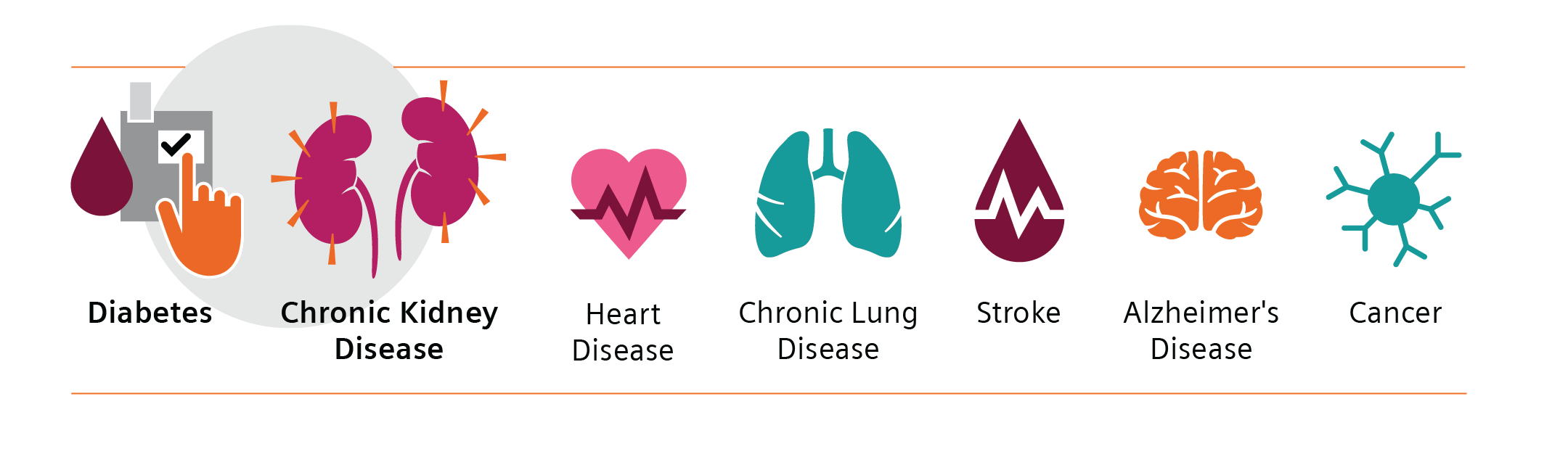

Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death and disability in the U.S. and major drivers of the nation’s rising healthcare costs.1 Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the top seven chronic diseases include heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). In the United States, 60% of adults have one chronic disease, and 40% are reported as having two or more.1 The costs of these chronic diseases account for nearly 86% of healthcare costs.2

Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death and disability in the U.S. and major drivers of the nation’s rising healthcare costs.1 Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the top seven chronic diseases include heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). In the United States, 60% of adults have one chronic disease, and 40% are reported as having two or more.1 The costs of these chronic diseases account for nearly 86% of healthcare costs.2

With these staggering statistics, chronic disease management has become one of the most important priorities for healthcare organizations today and the driving force behind value-based care: the measured improvement in a patient’s health outcomes for the cost of achieving that improvement.3

Value-based Care (VBC)

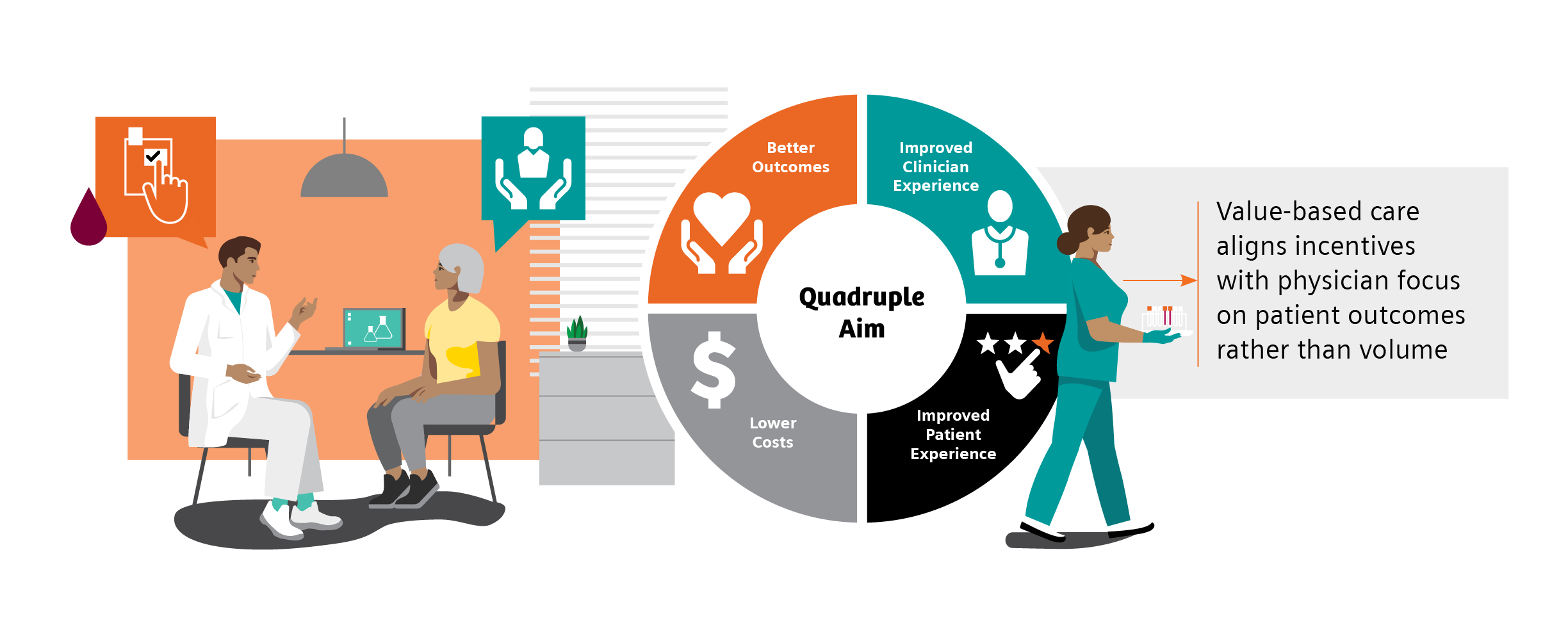

The goal of value-based care is to standardize healthcare processes and develop proactive best practices for patient care to prevent progression and avoid complications of disease before they start. The Value-Based Care (VBC) model centers around patient and provider accountability, shifting emphasis from fee-for-service.5 In this model, physician and hospital payments are based on patient outcomes, rather than volume-based metrics such as the number of patients seen, or procedures performed. The focus on patient outcomes is intended to help reduce healthcare costs while improving overall patient health and well-being.5

Patients seeking care for most of the high-cost chronic conditions, including diabetes and CKD, rely heavily on primary care physicians.6 In fact, primary care physicians treat at least 90% of patients with diabetes in the United States.7 Regular visits with primary care physicians can involve screenings, checkups, monitoring and coordinating treatment, and patient education to help manage chronic conditions.

Value-based care may provide earned financial relief to primary care practices while allowing clinicians to strengthen the rewarding patient relationships that are the backbone of primary care.8 In a joint survey by the American Academy of Family Physicians and CompHealth, 87% of providers said the best part of their job was “interacting with patients and helping patients.”9 Unfortunately, to achieve success in fee-for-service models, providers spend less time with patients, often addressing immediate needs but not underlying causes.9 Value-based care changes this dynamic, as it aligns incentives with the physician’s focus on patient outcomes rather than volume. Additionally, moving from a patient-volume model improves the experience of both the patient and physician, and may allow more time for valuable consultation.9,10 Overall, value-based care helps address the goals of the Quadruple Aim: better outcomes, lower costs, improved patient experience, and improved clinician experience.

Quality Measures and Quality Payment Programs

Quality measures are standards for evaluating performance when caring for patients. They are developed by both private and public-sector organizations and are generally based on the current clinical guidelines or literature reviews. Quality measures are used to not only benchmark individual clinicians and distribute bonus payments, but also to evaluate facilities, health systems, treatments, and care coordination.11 There are several quality-payment programs and performance-measurement sets designed to hold providers accountable for quality, assist in identifying opportunities for improvement, and monitor progress over time.

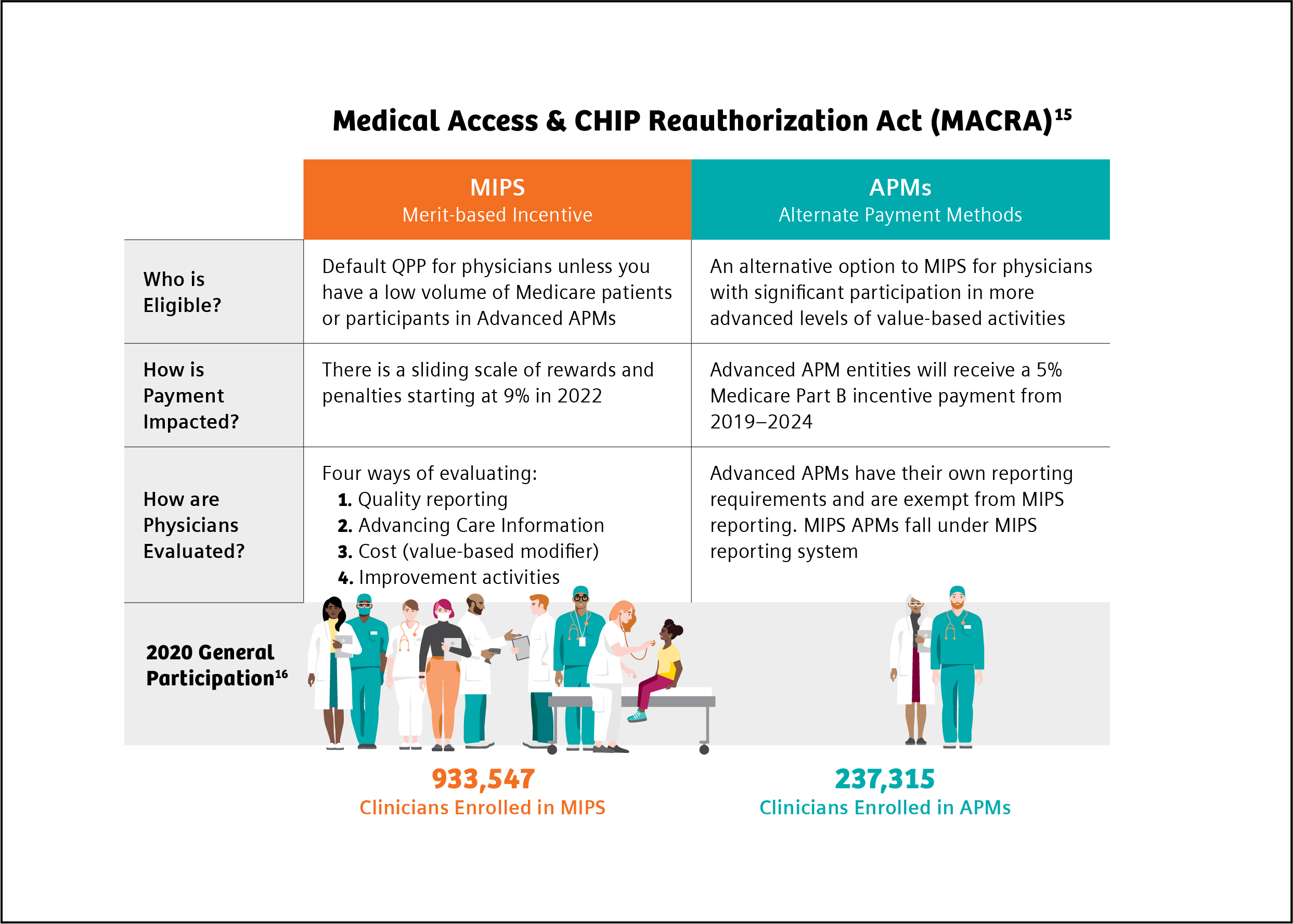

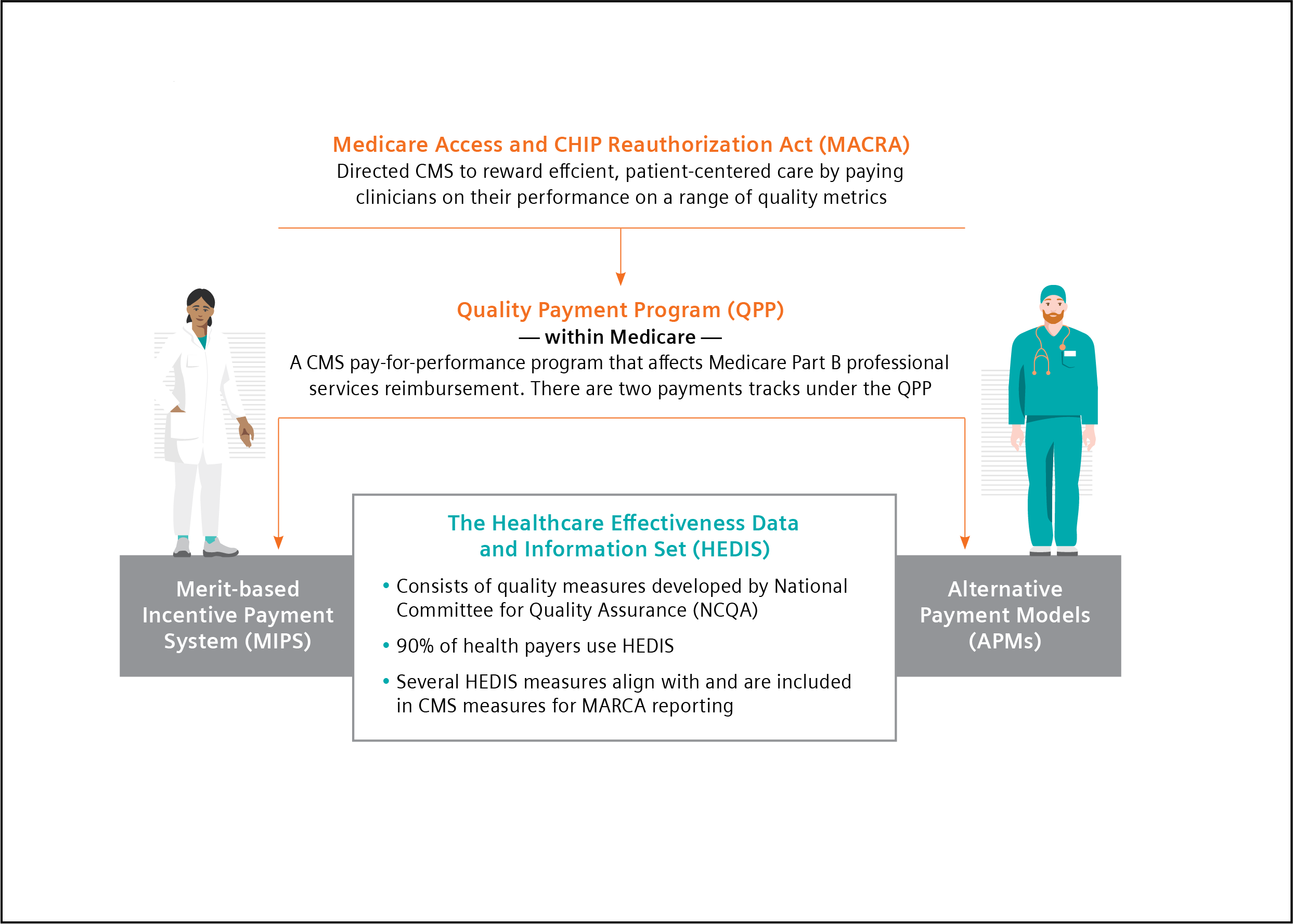

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is the largest payer of healthcare services in the United States.12 CMS is also the primary driver of changes in payment and delivery models and incorporation of value-based purchasing of healthcare services based on incentives.12 The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) established a physician payment system that incentivizes improvements in U.S. healthcare. Under MACRA, physicians participate in the Quality Payment Program (QPP), depending on eligibility, payment impact, and other factors, through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or through Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APM), such as risk-bearing accountable care organizations (ACOs).13

All eligible clinicians must choose to participate in either the MIPS or the APMs track and meet eligibility based on specific requirements.13 MIPS is the default program for all providers. In the MIPS program, providers’ performance is measured in four categories: quality, costs, the use of certified EHR, and improvements in clinical practice. Each category is weighted, and providers receive a score between 0 and 100.13,14 This score is then used to adjust payments. Under APMs, there are financial incentives related to the level of provider financial risk and the quality of care provided.14

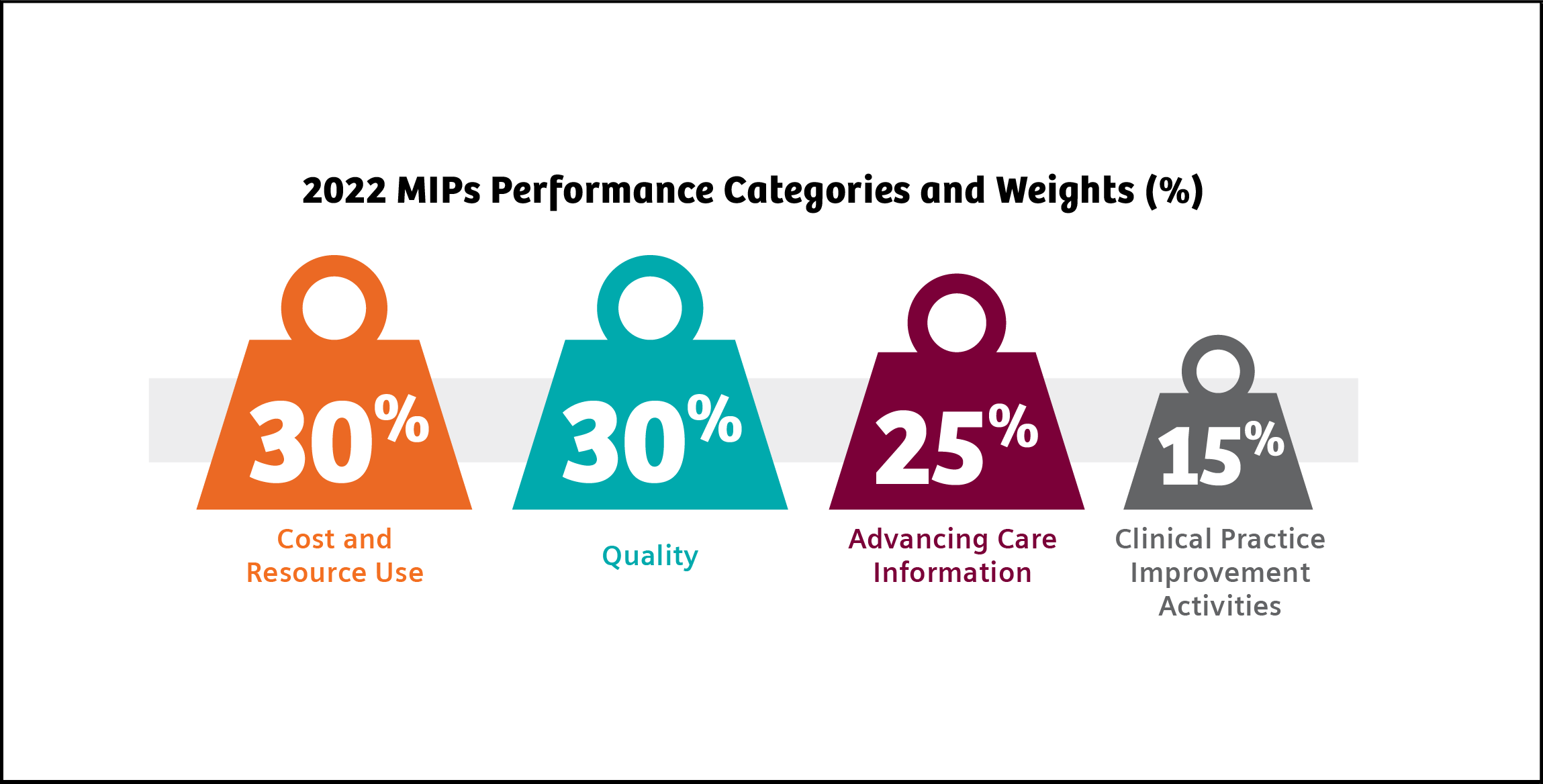

In 2022, MIPS scoring is weighted as follows: Quality (30%), Advancing Care Information (25%), Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (15%), and Cost and Resource Use (30%). The maximum payment adjustment for 2022 is ±9%.17

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) established a comprehensive set of standardized performance measures, the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), to give purchasers and consumers a way to reliably compare health plan performance.18 90% of U.S. health plans, including commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid health plans, use HEDIS measurement targets in determining quality incentive payments.18 Several HEDIS measures align with and are included in MIPS criteria.

Chart references 13, 18

Quality Measures in Diabetes and CKD

Diabetes is an ideal target for prevention strategies, as it is a major risk factor for other serious chronic conditions, including CKD. In the U.S., 37 million people are diagnosed with diabetes.19 This epidemic is responsible for an estimated $327 billion in annual medical and lost productivity costs.20

Additionally, 1 in 3 adults with diabetes also have CKD, responsible for more than $81 billion in annual Medicare costs.21,22 For those at risk for diabetes and CKD, early identification can prevent disease. For those with disease, early identification and treatment and routine monitoring can control disease progression and prevent related complications.23 On this basis, both diabetes and CKD are good targets for value-based care, where there is a desire to positively manage long-term outcomes while containing total cost of care in these growing populations. As such, diabetes and kidney health quality measures are often a focus of quality payment programs.

Guidelines call for routine testing of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and urine albumin-creatinine ratio (uACR) for disease monitoring and management.24,25 However, the literature demonstrates that only approximately 70% and 32% of patients with diabetes follow the testing guidelines for HbA1c and uACR, respectively.26,27

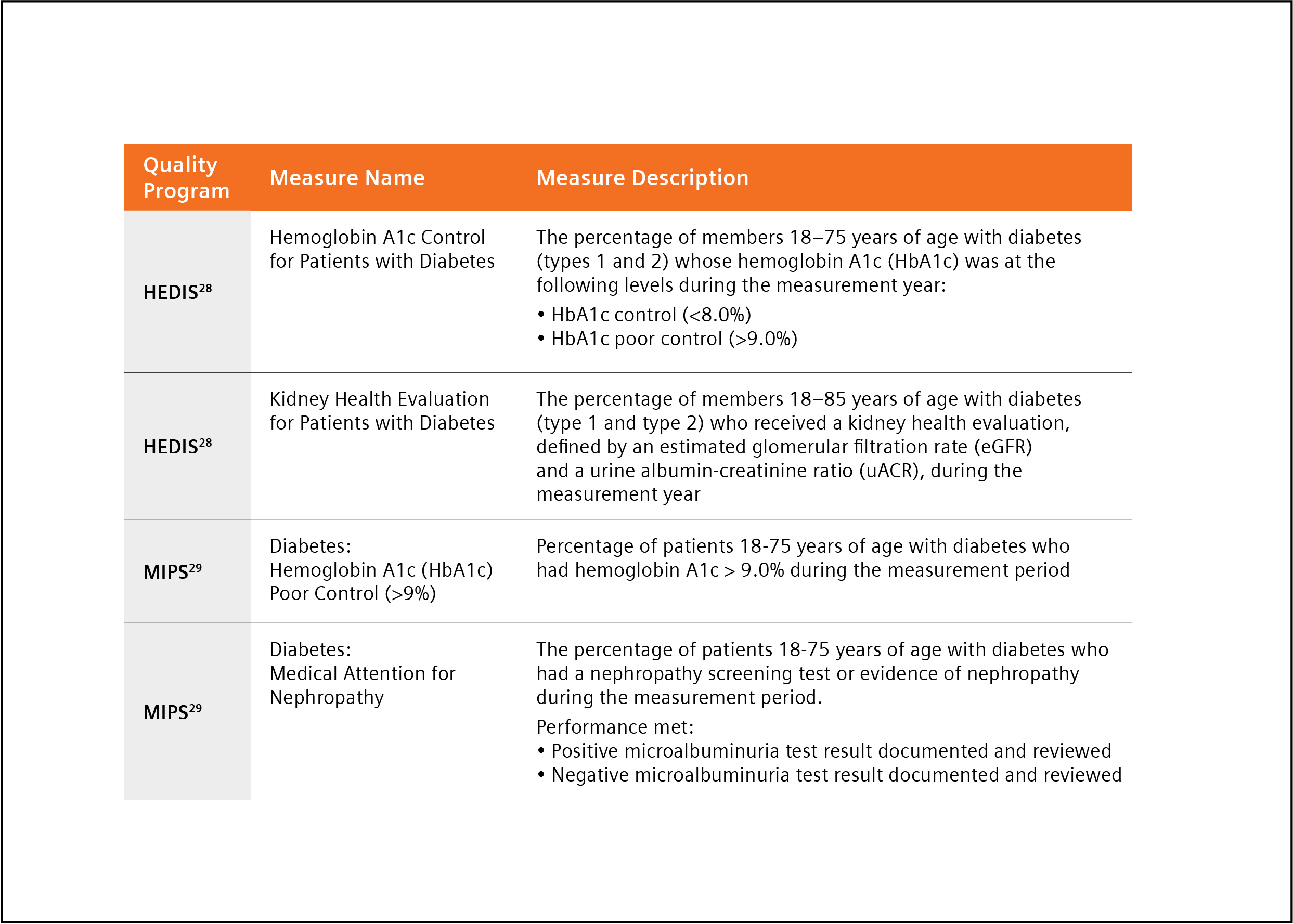

Key quality measures in diabetes care are HbA1c control for patients with diabetes and uACR for patients with diabetes and kidney disease.28,29

The population health challenge presented by diabetes, and the need for action, have been recognized for a long time. In 1998, to assess quality of care in diabetes management, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) led the first national effort to develop a set of performance measures for diabetes.30 These quality performance measures have since been widely adopted for assessment in Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial health plans, as a driver toward value-based care.31

Both MIPS and HEDIS quality measures for 2022 include measures for guideline supported HbA1c and uACR testing (Table 1).28,29

Table 1. HEDIS and MIPS 2022 quality measures for HbA1c and uACR testing.

A Path to Success in Quality Programs with Point-of-care Testing

Managing patients diagnosed with diabetes according to clinical guidelines is critically important, yet overall testing compliance is poor26,27 Point-of-care testing (POCT), clinical laboratory testing at the site of patient care, has been described as a quick, easy, reliable method for monitoring diabetes, and improving test adherence, in the primary care office setting.32 POCT enables the physician to perform diagnostic testing during an office-visit and affords the opportunity for immediate patient-physician consultation and intervention, eliminating potential loss and cost of follow-up associated with traditional laboratory (send-out) testing.32 In fact, the ADA has stated that “The use of point-of-care A1C testing may provide an opportunity for more timely treatment changes during encounters between patients and provider.”24

There is a growing body of evidence supporting the benefits of point-of-care testing to meet goals:

- A study by Crocker et al. demonstrated that POC HbA1c testing led to 3.7 times decreased likelihood of missing HbA1c 32

- A second study by Crocker demonstrated that point-of-care HbA1c testing “can significantly improve clinical operations with cost reductions through improved practice efficiency,” realizing a potential savings from improved efficiency of $24.64 per patient.33 This savings was achieved through a reduction in the number of calls, letters and additional patient visits required following implementation of POCT.

- A recent study by Christofides stated, “Access to uACR testing may be improved by using Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendments (CLIA)-waived point of care UACR testing options, that is, those approved for use closer to the patient and not necessarily in a central laboratory,” and noted that using a CLIA-waived POC uACR option was a means to optimize test ordering.34

- A study by Schultes et al. found that the implementation of uACR POCT in daily general practice can improve the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic kidney disease (DKD).35 The availability of uACR results at the time of the consultation led physicians to make medication adjustments to 18.5% of the patients enrolled in the study.35

The findings reported in these papers, and others they cite, suggest implementation of POCT may help busy practices achieve quality measures with increased testing adherence while decreasing operating costs through improved practice efficiency.32-35

Conclusion

The goal of value-based care is to cost-effectively improve patient outcomes. Value-based care models reward providers for efficient and effective patient care based on reported quality measures. Chronic conditions such as diabetes and CKD are ideal targets for value-based care because early detection and coordinated intervention can stop disease progression, improve quality of life, and reduce healthcare costs.

Quality measures in both diabetes and CKD are focused on guideline-recommended diagnostic testing. Adoption of point-of-care testing can improve test adherence while bringing increased value to patient office visits. Availability of real-time test results enables immediate consultation and faster intervention and treatment. This facilitation of care may lead to improved patient outcomes and decreased overall diabetes-related healthcare costs, meeting the goals of value-based care.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm#:~:text=Many%20chronic%20diseases%20 are%20caused. Accessed 4-13-22.

- Holman HR. The relation of the chronic disease epidemic to the health care crisis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020 Mar;2(3):167-73. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11114. Epub 2020 Feb 19. PMID: 32073759; PMCID: PMC7077778.

- https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/CHF-Winter-Spring-2017-Facing-the-Transition.pdf. Accessed 4-13-22.

- Petersen R, et al. Improving population health by incorporating chronic disease and injury prevention into value-based care models. North Carolina Med J. 2016;77(4):257-60. doi: 10.18043/ncm.77.4.257.

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/15938-value-based-care. Accessed 4-13-22.

- Sharma MA, et al. Patients with high-cost chronic conditions rely heavily on primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(1):11-2. doi: 3122/jabfm.2014.01.130128.

- Davidson JA. The increasing role of primary care physicians in caring for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(12 Suppl):S3-S4. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0466

- https://www.capphysicians.com/articles/overview-value-based-care-primary-care-practices. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://www.priviahealth.com/blog/how-the-quadruple-aim-and-value-based-care-intersect/. Accessed 4-13-22.

- Teisberg E, Wallace S, O'Hara S. Defining and implementing value-based health care: a strategic framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):682-5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003122.

- https://carejourney.com/physician-quality-and-why-it-is-important/ABCs of Measurement. Accessed 4-13-22. Error! Hyperlink reference not valid.

- https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Quality-Programs. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://www.aapc.com/macra/macra.aspx. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://checkpointehr.com/blog/difference-between-mips-and-apms/. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://www.myavls.org/member-resources/macra-resources.html . Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/1783/QPP%202020%20Participation%20Results%20Infographic.pdf . Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://mdinteractive.com/mips-blog/cms-releases-2022-mips-final-rule-key-takeaways. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/how-hedis-cms-star-ratings-cqms-impact-healthcare-payers. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/quick-facts.html . Accessed 4-13-22.

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917-28. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0007.

- https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/prevention-risk/make-the-connection.html. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://adr.usrds.org/2020/chronic-kidney-disease/6-healthcare-expenditures-for-persons-with-ckd. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://www.consultant360.com/articles/diabetes-and-chronic-kidney-disease-prevention-early-recognition-and-treatment. Accessed 4-13-22.

- American Diabetes Association. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021 Jan;44(Suppl 1): S73-S84. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-S006. Accessed 4-13-22.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee, et al. 11. Chronic kidney disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl_1): S175-S184. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S011.

- https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/library/Diabetes-Report-Card-2019-508.pdf. Accessed 12-17-21. Accessed 4-13-22.

- Alfego D, et al. Chronic kidney disease testing among at-risk adults in the U.S. remains low: real-world evidence from a national laboratory database. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(9):2025-32. doi:10.2337/dc21-0723.

- https://www.ncqa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/HEDIS-MY-2022-Measure-Descriptions.pdf. Accessed 4-13-22.

- https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures?tab=qualityMeasures&py=2022#measures. Accessed 4-13-22.

- Fleming BB, et al. The Diabetes Quality Improvement Project: moving science into health policy to gain an edge on the diabetes epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1815-20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1815.

- https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/34/7/1651/38635/Diabetes-Performance-Measures-Current-Status-and . Accessed 4-13-22.

- Crocker JB, et al. The impact of point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing on population health-based onsite testing adherence: a primary-care quality improvement study. J Diabetes Sc Technol. 2021;15(3):561-7. doi: 10.1177/1932296820972751.

- Crocker JB, Lee-Lewandrowsky E, Lewandrowsky N, et al. Implementation of point-of-care testing in an ambulatory practice of an academic medical center. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142(5):640-6.

- Christofides EA, Desai N. Optimal early diagnosis and monitoring of diabetic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: addressing the barriers to albuminuria testing. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211003683. doi: 10.1177/21501327211003683.

- Schultes B, Emmerich S, Kistler AD, Mecheri B, Schnell O, Rudofsky G. Impact of albumin-to-creatinine ratio point-of-care testing on the diagnosis and management of diabetic kidney disease. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021 Oct 28;19322968211054520. doi: 10.1177/19322968211054520.